The Atlas rocket is a favorite of the US military, but its manufacturer, United Launch Alliance (ULA), needs to drum up commercial business for it. How else but with a snazzy website?

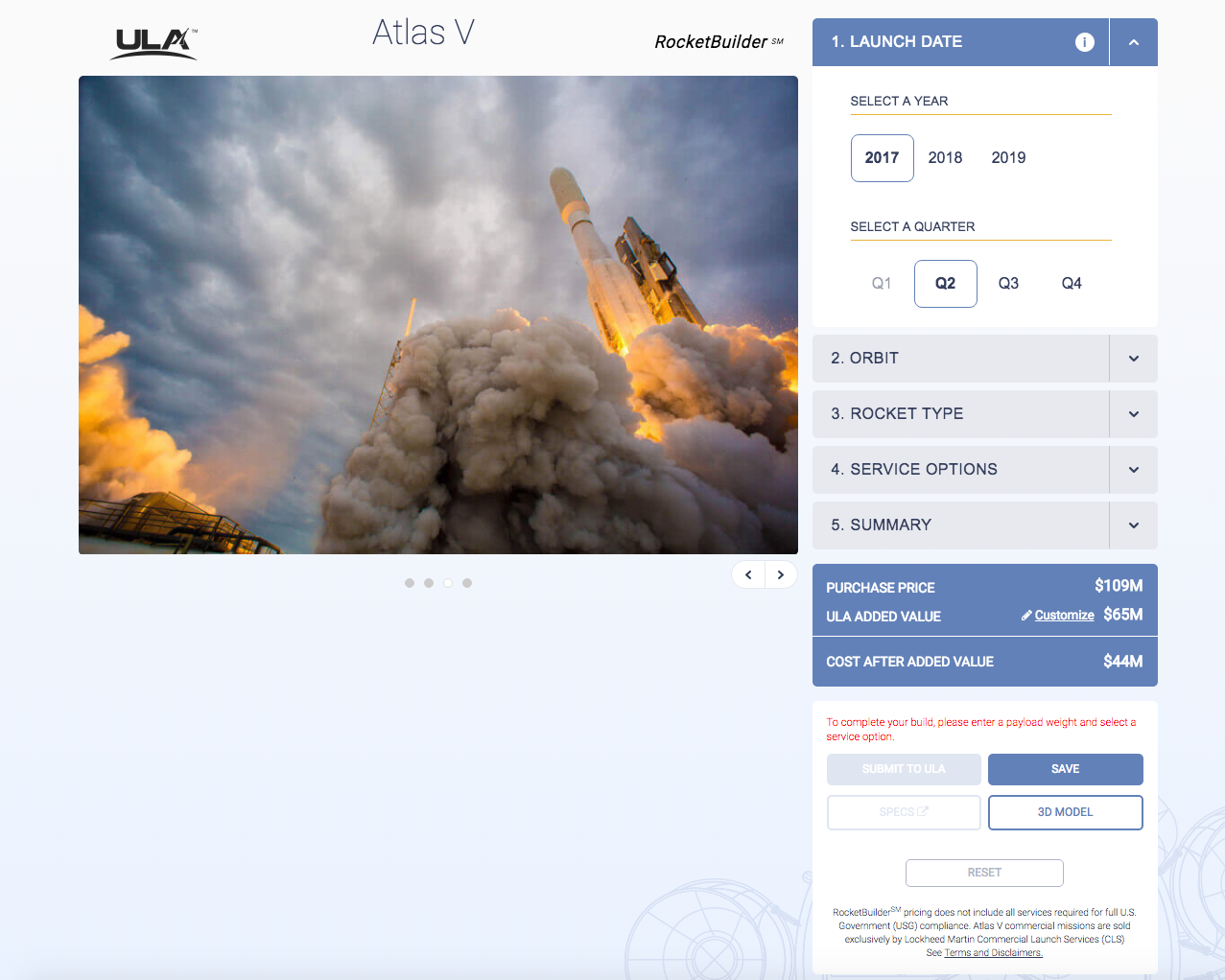

On ULA’s RocketBuilder.com, prospective customers can spec out the cost of their space transit needs, based on their choice of launch window, rocket type, orbit, and add-on services. If you’ve ever customized an automobile or a vacation package online, you’ll quickly get the hang of it.

“It will be easier to buy a ride in space than to get a plane ticket home for the holidays,” says ULA CEO Tory Bruno.

The RocketBuilder site was designed to demonstrate ULA’s orbital capabilities, and underscore its advantages versus its main US competitor, Elon Musk’s SpaceX.

Bruno took charge of ULA, a joint venture of Boeing and Lockheed Martin, in 2014 with a mandate to make it competitive with SpaceX, which adopted a Silicon Valley ethos of cost-cutting to drive down the price of space access and seized a big chunk of the commercial market.

It also began to make inroads on ULA’s previously exclusive work for the US Air Force.

Now, ULA is making its own push to win over more private business.

Booking a 2016 launch on ULA’s basic Atlas rocket costs $109 million—impressive by historical standards, but still quite a bit higher than the $62 million price tag on SpaceX’s Falcon 9. And, as some messing around with the tool will show you, the cost of an Atlas launch can increase depending on what orbit a client is seeking to reach and the size of their satellite payload. Ultimately, the tool is an instructive window into the pricing behind rocket launches, but it’s nothing the CFOs of satellite companies don’t already know about.

What ULA would like to highlight are its more intangible advantages, especially at a moment when SpaceX is still grounded after a September accident led one of its Falcon 9 rockets to explode during fueling, taking an Israeli company’s satellite with it. SpaceX hopes to return to flight with a December 16 launch of Iridium satellites, but is waiting on permission from the Federal Aviation Administration.

ULA claims that its unmatched reliability—Atlas rockets haven’t failed in more than two decades of launches—offers exceptional returns. It argues that its clients pay lower insurance rates, suffer from fewer launch delays (and the loss of revenue that accompanies them), and can place their satellites in precise orbits that allow them to remain operational (and revenue-generating) for as much as two years more than average. All told, these benefits can add up to $65 million in intangible savings, ULA says, though competitors dispute the ULA’s claims about its insurance rates and precision targeting.

The reliability bar, however, remains an important advantage for ULA. “Nobody chooses to have low reliability or blow their rocket up or be late; it takes a great deal of experience, process discipline and know-how to achieve this,” Bruno says. “Some day, I expect the rest of the industry will become as reliable as we are.”

These arguments are intended as much for media covering the never-ending cost battle between ULA and SpaceX as they are for potential clients. After all, satellite buyers in the cozy aerospace industry are aware of the benefits of reliability, and the risks of delay. But, judging by the two companies’ launch manifests, they appear to be equally cognizant of the benefits that come with saving $30 million or more on the purchase of a rocket, right now.

That’s one reason why ULA’s commercial business, marketed by Lockheed Martin Commercial Launch Services (LMCLS), remains fairly light: The company will launch just two commercial satellites in 2016, and has no commercial launches lined up for 2017, though Steve Skladanek, president of LMCLS, says the firm is “continuing to pursue launches for 2017 and beyond and believe[s] Atlas is the best choice for satellite operators who value date certainty and reliability.”

For comparison, SpaceX flew five commercial missions in 2016 before being grounded, and has more than a dozen scheduled in the next year.

But SpaceX is still, for the time being, grounded, and so ULA’s marketing push to commercial clients is designed to tilt the company’s odds at a time when its main competitor is most vulnerable.